Batman in the Bulletin

Keith wrote for the Bulletin monthly magazine under the pseudonym, John Batman, to avoid detection from his employer and commercial rival The Herald and Weekly Times.

This collection of articles from the Bulletin were edited by Keith's son, David, and published in 2004. Articles have been grouped into themes as below and include introductions, to explain the historical significance of the original writing.

In 1961 Donald Horne was editing a lively fortnightly The Observer, which he started in 1958. On October 19, famed Sydney newspaper tyro, Sir Frank Packer bought the Bulletin on behalf of Australian Consolidated Press. He called Horne and said, ‘I’ve bought The Bulletin. Which will we kill off, it or The Observer.’ This was a tough choice for Donald. Did he kill off his baby or did he kill off the oldest journal in the country. He chose to be editor of The Bulletin.

The Bulletin, of course, is Australia’s most celebrated and important magazine. It began on 31 January 1880 and depended heavily on lively, pithy contributions from its readers. In its early days it was ‘the journalistic javelin’, a vehicle for all manner of radical and nationalistic views. Under its founding editor, J.F. Archibald, it published such great names as the artists, Norman and Lionel Lindsay, Will Dyson, David Low, and writers, Henry Lawson, A.B. Paterson, A.G. Stephens and Joseph Furphy. By 1961 it was like an ageing relative, operating on a walking frame. It had been on the market for some time. It was losing money and its circulation had dropped below 30,000. Its masthead still carried the amazing message: ‘Australia for the White Man.’ It had the same pink cover just as it had back in the 19th century and the quality of its newsprint had never improved. The politics were archaic and Donald Horne wondered if any of the staff had been outside their front door in 40 years.Horne had two stints as editor. The first was for a year, then he went off to be a creative director for Jackson Wain Advertising, but his ambitions extended beyond producing advertising copy for big clients. It was during this time that he wrote his famous work The Lucky Country. He returned as managing editor in 1967 and remained until 1972. The new ‘Bully’ was almost unrecognizable from the old, and the cry of pain from loyal readers was huge. Eventually this subsided and Horne gathered a remarkable range of writers such as Max Harris, Geoffrey Dutton, Desmond O’Grady, Patricia Rolfe, Peter Hastings, a marvellous cartoonist in Les Tanner and the smartest Canberra correspondent, Alan Reid.

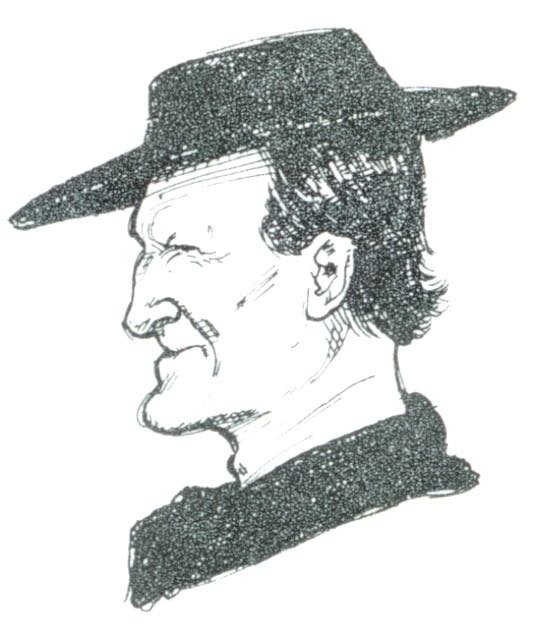

When Horne departed in 1961 Packer appointed Peter Hastings in his place. Hastings had come up through the Daily Telegraph in Sydney. He had been editor of The Sunday Telegraph and he had worked for Packer in New York. He did become one of Australia’s greatest experts on the politics of Indonesia and the Pacific. He was proud that he sat at the desk used by J.F. Archibald and looked up at the clock that had been in the Bulletin office for the past 82 years. He was a tall angular man with a large moustache, which gave him an appropriate Henry Lawson look. Horne in his autobiography Into the Open said that Hastings with his doleful face would have made a good model for Christ in agony. However, there was nothing Christ-like about Peter. He was a man of vast enthusiasms. He loved cognac, women, tennis, arguing, Joyce, Proust, D.H. Lawrence and hunting for bargains in second hand book shops.

Circulation under Hastings rose towards 40,000 copies a week. Not enough for Sir Frank who expected every ACP publication to make a good profit. Part of the problem was the location of The Bulletin. Always it had been published in Sydney. Naturally Melbourne treated anything published across the border with suspicion. Hastings thought it would be a great idea to have a Melbourne columnist, someone who could write a weekly piece, something like the London Diary in The New Yorker.

Hastings was an old mate. We had worked together as correspondents in New York. In 1962 after writing stints in London and Brisbane, I was writing a daily column for Melbourne’s Sun News-Pictorial. He thought I would be an ideal candidate. There was one problem. I worked for the Herald & Weekly Times Ltd and my chairman and managing director was Sir John Francis Williams the archrival of Sir Frank Packer, chairman and managing director of Australian Consolidated Press. Williams received his knighthood in 1958. Packer scored his in 1959. In the 1950s and 1960s any newspaper chief, who made sure that his editorial policy followed devotedly that of the Government, automatically received a knighthood.

Sir John had a rule that no member of his staff would write for any rival publication, nor would he, or she, appear on any rival radio or television program that was not owned by or associated with the H& WT. Peter was a crafty fellow and he saw a way around this. ‘We won’t use your name,’ he said. ‘Let’s see, we could call you “Batman”. He was Melbourne wasn’t he? Batman started it, he bought it from the Abos.”

‘Abos’ was one of those words you could say in the 1960s. I thought for a moment. Not for very long. He was offering 10 pounds a week, an enormous sum in 1962. I could try a different style. Sir John when he was editor-in-chief gave us instructions on how to write for the Sun News-Pictorial. He said: “Picture someone in Moorabbin. He lives in a triple-front brick veneer. He drives a car he doesn’t own. He spends most of his time watching TV and he has a mental age of fifteen. (It was always a ‘he’ in the 1960s) Don’t use words of more than two syllables. Use only the active voice and never let a paragraph go beyond 25 words. And remember, you have usually lost half your audience after the first par.”

It was the best advice I ever received, but I could make some modifications. My mythical character could live in a Paddington terrace house and I could throw in some words of three syllables and up the mental age to at least twenty.

This worked well for five years. There were a number of people who were not pleased with the use of Batman. Very early it became clear that Melbourne historians both professional and amateur were divided between those who thought John Batman founded Melbourne and those who thought the real credit should go to John Pascoe Fawkner. Why go for Batman at all? Some correspondents pointed to an entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography. Here was news that John Batman was not entirely the upright character described in our school books. He died of nasal syphilis and as for his wife, Eliza, she was ‘of somewhat abandoned character’ and was murdered at Geelong on 31 March 1852. Later on matters became worse when Professor Manning Clark began writing his History of Australia. Would it be wise to choose another nom de plume.

Manning Clark wrote: “Inside Batman was a man who abandoned himself wantonly to the Dionysian frenzy and allowed no restraint to come between himself and the satisfaction of his desires…When drunk he terrified those near him so much he would gladly give away all the fleeces of New Holland rather than expose himself again to the cruelties of a drunken Batman. His appetite for women was just as huge as his thirst for drunken oblivion.”

Less erudite correspondents wanted to know why we had chosen Batman, a character out of a comic strip, this dreadful creature, who kept dashing all over buildings wearing a mask. Furthermore his closest friend was a young male, named Robin. Why didn’t we pick some character, who wasn’t ‘a poofter.’ But it was too late. The name stuck.

There was a joyous freedom in moonlighting for ‘the Bully’. There was a series of editors, including Hastings, Horne, Peter Coleman and Trevor Sykes. Peter Coleman was an academic who came to the Bulletin when he was studying for a PhD. Originally, he had no experience in journalism but he learned with amazing speed. One had the feeling he never left the office. When he had a good idea he would ring at any hour of the day or night. One time he called at 1 a.m. and I said: ‘Peter, do you realise what the time is.’ He said: ‘No.’ He was still working at the office. Apart from the writing of many books and the editing of Quadrant he had a career in politics and became the leader of the Liberal Party in New South Wales. The Sun News-Pictorial had so many rules, so many terrors. Above all, we were a family newspaper and families always behaved with decorum, no bad language and there was to be no suggestion of sex. Sir John Williams even had a horror of false teeth. Perhaps it was a fear of decay and death, but there were to be no gags about dentures. It was like coming out of jail, with the Bulletin one could write as one pleased.

One morning in 1968 word came through that Mr. Daly wanted to see me ‘at once.’ Frank Daly was editor of the Sun News-Pictorial. When I entered his office immediately I noted the problem. He had a copy of The Bulletin on his desk. “You’re Batman aren’t you?” he said in a tone that might have been used to announce a traitor, at least a Burgess or a Maclean.

“Yes,” I admitted. “I am.”

It had almost ceased to be a secret. That winter, in the company of the Sun’s Foreign Affairs writer, Douglas Wilkie, I had launched the Anti Football League, which in the passing of four or five weeks gathered a membership even greater than that of the Collingwood Football Club. It was such an important happening Batman interviewed Keith Dunstan to discover what it was all about. One could describe it perhaps as the first example of editorial incest.

Daly thundered, but I couldn’t afford to leave Batman. After pleading destitution through the incredibly low salary paid by the Herald & Weekly Times Ltd. and the fact that only the generosity of Sir Frank Packer kept my four children at public schools, only then did Frank Daly begin to relent. He said the Batman column could continue, but only if it used stories that had already appeared in the Sun. That, of course, would have been impossible, but Batman Dionysian, queer or otherwise, continued for another 15 years.

The first Batman column appeared on March 3, 1962. It dealt with a number of sensitive matters concerning public morals. The Australian Swimming Championships were taking place at Melbourne’s Olympic Pool. It was clear that some of the costumes were disgusting, showing too much. Some young men were wearing togs size 26 when they should have been 32. The Amateur Swimming Union found one way around it. All winners and place-getters had to wear towels in front of their important parts on the dais when receiving medals.

Then, you see, it was the height of Moomba. For the first time the Festival had issued a permit for a beer garden, out in the open, if you please, in the Alexandra gardens. There were protests from temperance associations, the Methodist clergy and L.T. of Broadford wrote to The Age: “It seems to me that the present interpretation of Moomba is ‘Let’s get together and get drunk.’” There were worries too about the lack of intellectual stimulus in the festival. However, Batman revealed that the Coburg Ladies’ Pipe Band would be in action and there would be a dog competition with prizes for the best-groomed dog, the dog with the saddest eyes and the most intellectual looking dog. Would the Moomba committee please consider sending the intellectual looking dog as our representative at the Adelaide Festival of

Yes, Melbourne was a different place in the 1960s, as different as London is from Istanbul today. It had gracious Victorian period buildings, none of them more than six storeys in height. We used to refer to the area near Spring Street as the Paris end of Collins Street. Barry Humphries wondered wistfully whether the French ever talked of the Melbourne end of the Champs Elysees. Collins Street was indeed charming with some delightful plane trees but there the resemblance came to an end. The Oriental Hotel had a prime spot at the Paris end, where the Hotel Sofitel stands now. The Tewksbury family owned it and they thought it would be splendidly Parisian if they had tables and chairs out on the pavement. Good Heavens, no. Neither the City Council nor the Government would allow it. It was a sin in the 1960s to drink out in the open. That would lead to all kinds of untoward behavior. Furthermore it would be absurd even to drink tea outside, the weather was not suitable.

There was a different feeling, a lacking of confidence. Melbourne, like many a rich man, had an inferiority complex. Melbourne had been so deflated by the bank crash of the 1890s and the following depression; it was taking another century to get over it. The library at the Herald & Weekly Times had a plump file titled Melbourne – Criticism of. The public relations firms knew exactly how to get the front page for any visiting entertainer. Get him or her to talk about Melbourne’s insularity, its vulgarity, its sepulchral quiet, its liquor laws or its weather. The English singer, Max Bygraves, did well in 1965. ‘I’ve always wanted to see a ghost town. You couldn’t even open a parachute here after 10 p.m.’ Clement Freud, a travelling gourmet and a descendent of the famous Sigmund, wrote that Ronald Biggs hid away in Melbourne and drove a taxi. Why? Surely he would have had more fun in Dartmoor.

Knocking Melbourne was a popular pastime. If it wasn’t the Yarra, the miserable little river that flowed upside down, then it was the weather, the frightful Melburnian climate. This was curious because Melbourne has very nearly the ideal climate. It is closer to the equator than Madrid, Athens, Lisbon, all of France, most of Italy and most of Sicily. If you popped Melbourne into an equal position in the northern hemisphere it would be in the middle of the Mediterranean and closer to the sun than most Greek islands. Nor are we as wet as some of the other Australian capitals. We receive 657 mm of rain a year compared with 1029 mm in Sydney and 1148 mm in Brisbane.

Yet it was easy to understand why many of the young found Melbourne stifling. Six o’clock closing of hotels lasted until February 1966 and diners had to endure the misery where all glasses which contained alcoholic liquor were, by law, whipped off restaurant tables at 8 p.m. Although all but three or four eating establishments in the city sold execrable food dignity had to be maintained. Anyone not wearing a tie was asked to leave and no woman entering a dining room could wear slacks. Sheila Scotter, fashion leader and editor of Vogue was asked to leave when she entered the dining room of the Southern Cross Hotel. She was wearing a gold lame pants suit. Her ejection was most surprising. Sheila Scotter looked very good in a gold lame pants suit.

Women had a hard time. Until the mid-1960s the Australian pub was a monastic institution. There were female lounges usually with Spartan tables and chairs. The ladies sat down to be served and paid dearly for the privilege. It was a sin, almost indicating prostitution, if a woman entered a pub without an escort. Even as late as 1969 the unescorted lady was something to be feared. When granting a licence for a new St Kilda cabaret Judge O’Driscoll warned the nominee: “The commission will not tolerate women attending without an escort.”

The public and saloon bars were all male and no female was allowed in. We didn’t even like barmaids in our hotels. Victoria did not go as far as far as the South Australians who banned them by law until 1967. In Victoria only the licensee’s wife, daughter or sister was allowed behind the bar.

It was a difficult time. Book censorship was all the go. We could not read the D.H. Lawrence classic, Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Even the report of the London court case, The Trial of Lady Chatterley, was banned. We had a famous Chief Secretary, Arthur Rylah, who was a specialist in these matters. The Vice Squad seized copies of The Group by Mary McCarthy. Sir Arthur said: “If I had a teenage son or daughter, I would not like to see them reading it.” Parliament discussed The Group at length, describing all the most exotic passages. The answer was obvious. There was no need to purchase Ms McCarthy’s book. All the best parts were available in Hansard, price fourpence a copy.

If one really wanted sin then one went to New South Wales. Victoria had no gaming machines, no one-armed bandits. Thankfully there were machines by the thousand in clubs just across the border. Towns like Barham, Moama, Corowa and Albury thrived by filtering money from the pockets of wayward Victorians. In the 1960s and 1970s we thought Sydney was the capital of sin, the most depraved city in Australia. We were so intrigued by the low standard of morals, the gambling, the corruption, many of us could hardly wait to get there. For several decades Melbourne bus companies offered “Sydney Night Life Tours.” They left on Friday night then they would arrive in time to take in the full culture of Kings Cross of bare breasts and bodies, gambling legal and illegal, then return to Melbourne in time for sober work on Monday morning.

Sydney was the first city sufficiently depraved to put on the Musical Hair, which showed human bodies, male and female, totally unclad. Once again the bus services provided special Hair tours. So over 200,000 Melburnians were able to have themselves shocked before the show came to Melbourne.

The Melbourne Sunday was considered by many to be so perfect, it was a work of art. There was no sport, no movies, no theatres, no restaurants, no newspapers, no shops. How did one put in the day? There was the Zoo, there was the Botanic Gardens and one curious pastime that was extremely popular, tour out to Essendon airport and watch the aeroplanes landing and taking off. The Victorian Football League, as it then was, wanted to commit the ultimate sin and play league matches on Sunday. A series of Victorian Governments would not allow it. Relief did not come until 1979 when the VFL started playing football on the Sydney Cricket Ground. This made it possible to switch the sin to Sydney, but at the same time we could watch the game on Melbourne television, on Sunday.

And yet…and yet, it is still possible to look back upon the sixties with nostalgia. Money had not taken over sport entirely and there was a still a sprinkling of amateurs. Football was still a suburban thing. People were loyal to the teams in their own area and they actually played on their own grounds: Footscray at Footscray, North Melbourne at North Melbourne, Hawthorn at Hawthorn, Essendon at Essendon and glory be, Collingwood at Collingwood.

The public schools had their boat race on the Yarra. It was a spectacular and glamorous affair attracting crowds as if it were the Melbourne Cup. Alas, the headmasters decided it was bad for the young men. On boat race night the school crews used to appear to cheering crowds at the local theatres. They were being turned into Gods. So righteous headmasters banished the race to Geelong and even that was not far enough. Now it is at Nagambie.

That dreadful word ‘affordable’ did not exist in the 1960s, but crayfish certainly was and my mother remembered buying them at Lorne for a shilling. There was a wonderful bar just behind the Port Phillip Hotel, opposite Flinders Street Railway Station. Here you could buy oysters with bread and butter for lunch two shillings and sixpence a dozen. If one wanted to go on a pub-crawl it was an interesting exercise, in Bourke or Swanston or Flinders there was no need to walk more than 50 yards before finding a suitable well. We saw the exit of all the great ones, Menzies, Scotts, the Federal, the Oriental, the dear old Port Phillip and the Occidental. At the Occidental you could get a very good Irish Stew and easily the best counter lunch in town. According to legend Nellie Melba once slept at the Occidental, but then according to legend, Nellie slept almost everywhere. The Reserve Bank tower now occupies the space, a regrettable building that has no Irish Stew and is no use to anyone who is hungry.

One misses so many buildings. For example, on the corner of Exhibition and Bourke we had the Eastern Market and like all good markets it was a labyrinth of this and that. It dated back to when Melbourne was young. Once it housed phrenologists, fortune-tellers, magicians and the extraordinary E.W. Cole of Coles Book Arcade began there. In the sixties it still housed a wonderful second-hand bookshop and a hardware business. That’s another thing, hardware has fallen on evil times. This place had its own individual musty smell and old gentleman who would take time to sell you an individual screw or a rare type of hinge exactly suited to the front gate. One would get lost just browsing in the Eastern Market and arrive back half an hour late for work. The Eastern Market came down to make way for the very smart Southern Cross Hotel. That didn’t work and now in 2003 the site is a hole in the ground waiting for another absurd tower. Could we not arrange finance and return the Eastern Market to the site.

Melbourne Mansions was another, a charming building composed of gracious apartments, many of them owned by Western District graziers. The gentlemen graziers occupied them for the entire Spring Racing Carnival. Mr. Jonas had his famous fruit shop down below, recognised as the best fruit shop in Australia. Alas, he and Melbourne Mansions had to go to make way for the CRA building, which looked like an ice block tray pulled out of the ground. The ice block tray made way for a larger set of ice blocks, 101 Collins Street, even uglier than its predecessor. I think we could also recycle 101 to get back Mr. Jonas and Melbourne Mansions.

Whelan the Wrecker pulled down so many great buildings in the city. The proprietor was Jim Whelan, a big gruff man, and although it was his living, he had mixed feelings about what he was doing. He filled his office with relics, including splendid pieces of marble, which he took from the Colonial Mutual Building at the corner of Elizabeth and Collins. This was built in 1893 and Jim thought it the most magnificent building ever erected in Melbourne. He thought it a tragedy that it ever had to come down. I asked him what he thought about the modern buildings, for example, the CRA building. He immediately became enthusiastic.

“Oh yes,” said he. “We could fix that. Easy! You would start at the top and work your way down. Just like taking apart a piece of Meccano.” So that is exactly what happened, except it was nigh on 20 years later. If Jim were still here he would adore to pull down number 101.

There is much to look back upon with nostalgia. In the 1960s the wine boom had not started and our politicians had not discovered how easy it is to finance almost everything through gambling and drink. There was no tax on wine. It was possible to buy excellent bulk wine and bottle it for a shilling a bottle. Jimmy Watson at his establishment in Carlton sold Madeira for threepence a glass.

The automobile made extraordinary advances in efficiency, but life became less convenient for human beings. In the 1950s and 1960s almost everything was home delivered. There were still horses in Melbourne. The milk was delivered at 6 a.m. by horse and cart. The baker delivered the bread and left it on your doorstep. The butcher delivered his meat and all the great stores, Myer’s, Buckley & Nunn, Foy & Gibson, the Mutual Store, Ball & Welch, and Georges delivered and there was no charge.

The automobile had not begun to strangle our streets. The parking meter did not exist. Yes, we did have a rather timid 5 o’clock rush, but now there is the 4 p.m. to 7 p.m. strangle, which is preceded by the 3 o’clock rush where mother has to collect her child from school in the four-wheel drive. Children in the sixties walked or used public transport. Trams did much better business then and they ran every five minutes. A single section cost threepence, paid for with a small silver coin.

The suburbs were quieter, more peaceful. There were no mechanical blowers, no chain saws, no brush cutters and there was a lovely ritual in the autumn. We would sweep up the fallen leaves in the street, put them into a pile and burn. You can’t beat the autumn smell of burning oak or plane tree leaves. So you stand there with your rake and chat to your neighbor who was also burning his leaves. You are not allowed to do that any more. Come to think it, we don’t talk much to our neighbors either.

Bring back the palaces

Television had one deadly and terrible effect and that was the ruin of the picture palace. Back in the depressed nineteen thirties the palaces were our saviour, our glimpse of luxury and satisfying make believe. Our palaces were huge and very nearly the finest on earth. If one was well-to-do it was done to have to have permanent seats, always there, in the dress circle at the Capitol, the Regent or maybe the Palais at St Kilda. If one was young the ultimate was to be invited in a school party to the State Theatre in Flinders Street where they had Rudolf Valentino's sword in a glass case and there were stars and scudding clouds in the ceiling. Some theatres could hold an audience of 3000 or more and part of the fun was to gaze upon celebrities who were bound to be present. Not any more. Now theatres are the size of small restaurants, boxes, and they put six in the one building.