Demonic people

First published

Henry Lawson was a little too fond of the Demon and there are some marvellous Lawson quotes, but my favourite is this. He said the greatest pleasure he ever knew was when his eyes met the eyes of a mate over the top of foaming glass of beer. The demon is a wonderful catalyst, a magic ingredient for mateship and some of the most generous, remarkable people I have met have been in the liquor industry.

Oh, there have been exceptions. There was R.F.G. Fogarty, managing director of Carlton & United Breweries. Fogarty was the last of the beer barons, as near as you could be to a dictator in Melbourne. Victorians liked Melbourne beer and he knew it. He would not tolerate anything else. Behind his back he was "Old Foge" but nobody dared call him Foge to his face. He was MISTER Fogarty or "Sir".

He was a very tough operator. Trading terms with Carlton & United was seven days. If a hotel did not pay within that time no more beer would be delivered and in Victoria that meant ruin. If there was a beer strike and a licensed grocer or suburban hotel attempted to bring in, say, some Emu, West End or Tooheys from interstate, that would be death. Foge would put out the warning if a hotel or a licensed grocer brought in one foreign bottle or can, the sweet relationship With CUB was finished. No more Carlton beer would be delivered, ever. Nobody was brave enough to defy that edict. How could a liquor dealer survive in chauvinistic Victoria if he did not sell his Foster's or his Victoria Bitter? I made the mistake of thinking Foge was my friend. He would call me at the Sun News-Pictorial when CUB was putting a new product on the market. It was in 1964 or 1965 that the Brewery introduced a new 750 ml can of Foster's Lager and Fogarty telephoned: "Would you like an exclusive story?" Would I, indeed.

I rushed to the Brewery, was ushered into Mr Fogarty's Spartan office. "This is our new product," he said. "You can take it away and write a story about it." It was hardly the scoop of the century. Foster's had been in cans for some time. Now it was merely coming out in a can double the size. So I took Mr Fogarty's new creation. It was an empty display model. Old Foge did not perform rash deeds like giving away full cans. And so I took it back to the office.

It was a problem. How did one display this inanimate thing in a daily column? The picture editor, Pedler Palmer, suggested that we get Lou Richards, ex-Collingwood footballer and licensee of the Phoenix Hotel, to hold it as if he were just making the first sale. And so it appeared in the Sun News-Pictorial the next day.

Three months later I was at the Duke of Wellington, the next pub down Flinders Street from the Phoenix. CUB was spending money to bring it into the 20th century. The publican told me it was one of the oldest pubs in Melbourne and, one time, cockfighting took place in the cellar. That seemed a good story. Why not call my old mate "Foge", he would tell me about it. I rang CUB, asked to speak to the managing director and back came the reply: "Mr Fogarty doesn't want to speak to you." No niceties like Mr Fozarty is not available.

So I tried the assistant general manager, Brian Breheny. He was in conference. I tried the head brewer, Carl Resch. I went round the entire building and everywhere the story was the same, nobody could come to the phone. Finally I called the public relations chief, Ginger Burke. Ginger had been in the Army with Fogarty and was said to be his closest mate. He said: "Sorry Keith, the Old Man has putout the word that nobody in the brewery is to speak to you."

"Why?"

"He gave you a story about his new can. You put it in the paper with Lou Richards. He doesn't like Lou Richards, so you're finished."

Fogarty died on 27 February 1967 and an amazing era started. Brian Breheny was the new top executive and a new era began. An unheard of thing took place. There was a party for the press at CUB. When it was over, as the guests went through the door, Brian Breheny personally handed each one a case of beer. When it was my turn, he gave me a long look and said: "I think you deserve two cases."

There were many who taught a simple student about the wonders of the Demon. Perhaps the wisest of them all was John Brown of Milawa, already mentioned in this story. One of the earliest was Jimmy Watson, who created one of Melbourne's institutions, an icon to be compared with Captain Cook's Cottage, the Long Room at the Melbourne Cricket Ground or Chloe at Young & Jackson's.

As Dr Sam Benwell pointed out in his little classic, Journey to Wine In Victoria, in 1890 there were so many vineyards in Victoria a special committee of inquiry was set up to advise on them. It recommended the division of Victoria into three wine regions: "From the south - Geelong, Whittlesea, Lilydale and Sunbury - should come the more delicate wines, chablis, white hermitage and the rest of the blonde beauties. Then from the north - Rutherglen and Wangaratta - would come the heavy artillery, the ports, the sherries and the muscats. From central Victoria would come the clarets and the burgundies." As Dr Benwell put it, when Queen Victoria died, Victoria's viticulture very nearly died with her. Phylloxera and the equally devastating effects of a great depression wiped out vineyard after famous vineyard.

With all this bounty of wine, of course, there were wine saloons everywhere. But as soon as the wine declined so did the saloons. In 1917 there were 273 wine saloons in Victoria. By 1935 there were only 159, immensely disliked both by the police and the Licensing Court. Rapidly they were closing down. Originally the theory was the wine bar would encourage the sale of fine Australian wine. It never happened. Those interested in wine bought from select dealers. The wine bar was the home for "steam and bombo", the refuge for the outcast and a last resort for the wretched during the 1930s depression. Here it was possible to end all worries with a glass of insidious port or what was known as the fourpenny dark.

The Government closed most of them down by an act of parliament on 31 December 1963. The wine bars either had to convert to licensed restaurants or go out of business. There was a terrible cry of pain from the saloon keepers. The things they said about Judge Fraser of the Licensing Court would have blushed the cheeks of polite people to a shade of cabernet. Our saloons fill a need, they said. Who will look after the poorer classes now? You see, the sale of methylated spirit will go up.

Into all this stepped Jimmy Watson. Actually his first love was music and his ambition in life was to be a great flautist. He trained under Claudio Amadio. But the depression was not good for musicians and young J.C. Watson made his living working in a theatre orchestra. In the days of the silent movies it was young Jimmy who helped to play the silent hero across a silent screen to save a silent heroine.

Talkies put an end to this career. In 1935 he decided that he would like to teach Australians how to drink and enjoy their own wine. So he bought a wine bar, not in a nice suburb like South Yarra, but a few doors from a brothel in the wine-bum area of Lygon Street, Carlton. Few people thought he would last a month, particularly after he had thrown out all the best customers, the plonkos. But as long as the customer wasn't there drinking for oblivion, he had a friend in Jimmy. There was such a thing as a "threepenny madeira" and it was always available for the needy. The price never went up and when things became too quiet in the bar, Jimmy would call out "Oooll have a threepenny madeira?"

He was large and hearty and, although his private wealth was quite considerable, always wore a large leather apron, the type used by the drivers of brewery wagons. His gift to us was his knowledge of Australian wines. He used to buy by the hogshead and sell that wine at four shillings a bottle and sixpence a glass. He didn't tie himself to any of the wine houses. There were no proprietary wines in the place and he refused to sell by the flagon..."If you do that the galahs only take it home and expect it to stay good for a week." Rapidly he picked up a marvellous trade from the University and later half Melbourne. One would have to think carefully before having lunch at Watson's because it was so easy to fall under Jimmy's spell. "Have you tried this shiraz from Rutherglen? You'd better have a look at the latest from Purbrick." It was only with considerable difficulty that one could get back to the office by 4 pm.

He had little patience with wine snobs. In her book, Jimmy Watson's Wine Bar, Grania Poliness tells the story of the character who came in and announced he was a member of the Good Food and Wine Club. He wanted some wine to lay down and he needed to look at some good reds. Jimmy brought down a bottle from the highest shelf, polished a glas, and poured. The 'expert' sniffed, hahhed, mmmmed."An excellent claret," he said.

"That's interesting," said Jimmy, "because it's a burgundy. I'll go and get the claret now." Jimmy Watson died far too young on 22 February 1962. There were various reports on how many people turned up for the funeral service at St Jude's Church of England in Carlton, but one newspaper put it at over a thousand. There were crowds up and down Lygon Street. The cortege paused for a moment at number 333 the most famous number in the street, and local traders closed for the day.

The regulars at J.C. Watson's thought so much of him they collected 700 pounds for an annual trophy at the Royal Melbourne Show, which still remains the most valued prize for young reds.

His son Allan was only 27 when Jimmy died. Allan was brave indeed. He threw out the dreadful old pictures. The celebrated architect Robin Boyd redesigned the place inside and out. There were only two colours, white and aubergine. This aubergine was a matter of great research. They wanted a colour that looked just like the inside of a wine vat. All this caused a cultural shock amongst the old hands.

But Watson's thrived and became better than ever. Allan changed the policy carefully laid down by his father. No proprietary brands, buy in bulk, bottle cheaply and sell by the glass. No nonsense, no snobbery, good wine and good food. Like his dad, he tends to forget to pick up the money, and the task of getting back to the office by 4 pm is no easier. Jimmy Watson was unforgettable, but then so was Eric Purbrick. My fondest memory of Eric is that old brewery barrel.

Eric found it in 1962 or 1963, a cast off from the Carlton brewery. Carlton had shed all its wood and now it was dealing more crudely in stainless steel. It was typical of the generosity of the man, he would fill this barrel with his precious Chateau Tahbilk shiraz, and send it down by train to Melbourne.

Wonderful it was. We would get precisely 108 bottles to a barrel for around a shilling or 10 cents a bottle. That barrel kept going until, like the rest of us, it became creaky with age. But let me tell you about Eric. He had style, an elegance, which was a little unusual for the wine industry. He loved old silver, he loved pewter and he loved his vintage Rolls-Royce. He drove that Rolls at a steady 35 mph, never looking to left or right, always with 20 frustrated motorists panting behind.

He was educated at Melbourne Grammar, then followed on to Jesus College, Cambridge. He left college in 1925 and in 1929 was admitted to the bar of the Inner Temple in London. He was a good tennis player and a great cross country skier. There is a story that while skiing in Europe he fell down a crevasse. A ski, stuck in the ice, saved him. The newspapers of the day reported that the very calm young Mr Purbrick smoked a cigarette while waiting for the rescuers to haul him out.

Mercifully he did not waste his life on the law. He was in Germany when his mother suggested that he should come home and manage a very run down Chateau Tahbilk. So he returned and had his first vintage in 1931.

He knew not a thing about winemaking and he had to learn it all from books. What's more, Australia was a beer loving country and in those depression days he had to hawk his wine around pubs and wine dealers, selling it for a mere shilling and twopence a gallon.

Eric was determined that Australia should not lamely follow France or any other country. He would have none of this business of labelling wines hock, claret, chablis or burgundy, Hie insisted that Tahbilk wines would be labelled for what they were, after the grape and precisely where they came from. In this he was a pioneer.

As for the name, Tahbilk. Tahbilk is Aboriginal, meaning 'many water-holes.' So it seems bizarre mixing up 'Chateau with an Aboriginal name. Yet somehow it is more like a French chateau than anything in France. Eric and his wife Mary turned the old cellars, the house and garden into a work of art and it became the most beautiful vineyard in the country. Many still remember 25 September 1960 the day they invited Sir Robert Menzies to celebrate the Tahbilk centenary. Way back in 1876 the first owners preserved a cache of bottles in the cellar wall. Eric asked his old friend to do the same, to brick up a bottle of dry white and a bottle of dry red, not to be opened until the year 2060.

Sir Robert was in one of his best ironic moods that day. "Of course, you all know I am practically a teetotaller. So it is with the greatest of pleasure that I deprive drunkards to the extent of two bottles. Yes, two bottles are safely out of harm's way," said he, as he wielded his trowel.

However Sir Robert made no mention of the splendid quantities of champagne which were not out of harm's way, and he proceeded to deal with that personally before the day was done.

Tahbilk wines under Purbrick's guidance were, and still are, sold all around the world. In recent years he developed a very close relationship with his grandson Alister, who became Eric's winemaker.

When Eric died in January 1992 Alister spoke lovingly of his grandfather yet it was a relationship not without battles. Alister returned to Tahbilk with his winemaking degree, determined to create a new era. He installed all sorts of modern equipment and brought Tahbilk whites forward into the 90s.

Eric went along with that but when Alister wanted to change the reds there was trouble. The battle went on for three years. Alister said every time he suggested changing the red wine style, Eric very craftily would sit him down and open a very good bottle of red. For what seemed the umpteenth time he tried again.

"Grandfather invited me into his private cellar and opened the mandatory bottle of red wine. Then he suggested I go through my plans once again, which I did with considerable bad grace, knowing he had heard the same story many times before. When I finished he asked me what I thought of the red, which was a '62 cabernet, and perhaps the greatest wine he ever made. I waxed lyrical about the wine. Well my boy,' he said, 'if you like this wine and all the others so much, why the hell are you bent on changing the style?' "I thought about that. He had me checkmated. He was quite right and it was left well alone."

Eric had a great relationship with Len Evans, dating back to the time when Len was working for the Wine Bureau. It was in the 60s that Len visited Tahbilk during vintage. Everyone was on the job with no time to look after visitors. So Len decided to take over as tour guide. He ran on brilliantly about the "new cellars" built in 1875, about the mysterious bulge in the corner which appeared to endanger the building, but, not to worry, it had given no trouble these past 90 years.

Then he noticed Eric Purbrick, shovelling grape stalks out of a crusher de-stemmer. "And here we have one of the typical workers," said Len. Eric worked on taking no notice.

"They are simple peasant types. They don't speak English. In fact we don't even pay them. We shovel the food in one end and they do the shovelling with the other."

The tourists were becoming increasingly embarrassed. As they moved on, Eric picked up a fork full of mess out of the de-stemmer and hurled it at Len. It hit the wall just over his head.

"Are you sure he doesn't understand English?" one of the tourists asked.

When Eric died, Len attended a memorial service which Mary Purbrick, Eric's wife, arranged in the beautiful Chateau Tahbilk Garden. Len told us what Eric had done for the wine industry and the great standards he had maintained at Tahbilk. He said: "1903, the year Eric Purbrick was born was not a very good year for Madeira. When we attended his 80th birthday, I brought what was actually a bottle of the 1900 vintage, the last stencils of the letter was cut out and carefully corrupted and presented it to him for that night. Although he went through that dinner party with enormous abandon and great relish we actually didn't get round to drinking the Madeira. "What about next year? Will I come down?"

"No, I don't think so, just wait until I am 85."

"Do you think you'll last that long?" I said.

"Yes old chap I intend to live until I am 88."

"He did exactly that, he lived until he was 88."

As for liquor sales there were two giants in our district, Dan Murphy and Doug Crittenden, different in style but both intensively competitive. Dan was in Chapel Street, Prahran and Doug was around the corner in Malvern Road, Toorak. Dan was more of a private person, introspective and often withdrawn. Doug was the grocer, gregarious, the man who liked to serve behind the counter and knew everybody. Both were born to the trade, their parents were in it before them.

For the Murphys tradition began with Dan's grandfather who had a hotel in Footscray. Dan's father and three brothers had stores in Auburn, Bridge Road, Richmond, and South Yarra. Dan began very early, aged 10, bottling wine in the cellar at Allgoods Store in Burwood Road, Hawthorn. The bottling system could hardly have been more primitive. There was a hogshead with a plastic tube fitted on to a wooden tap. Put the tube into the bottle and when it reached the right level, squeeze. Dan insists he became quite expert and not too much flowed on to the floor. The next move was to put the corks into the bottles with a hammer.

There were different colors of silver foil to denote whether it was muscat, port or dry sherry. It was also a hand job to put on the Murphy labels. This he did with a pot of paste. Oh no, there was very little dry red, nobody drank much of that until the late 1930s. A bottle of port cost ninepence and a bottle of claret fetched sixpence. There was nothing in it for the grower, according to Dan. That is why so many went out of business. The wine producers were selling whites and reds for ninepence a gallon. It was easier to pull up the vines.

The Murphys, of course, were Irish and strict Roman Catholics. Dan was confirmed at the age of 12, and took the pledge promising not to drink before he was 25. This was not uncommon. All Catholic families were taking the pledge.

Dan left school early and at the age of 16 went to work for Penfolds. He delivered liquor by bicycle all around Toorak and South Yarra. He had a basket on his handlebars. As he puts it, one learns a great deal about balance when carrying bottles on a bike.

But then Dan decided he want to be a priest. He went back to school for two years, then he went to Sydney for four years to train with the Franciscans. "But I couldn't stand the life," says Dan. "It didn't suit me at all. The order was completely dominated by the Irish, so I quit, joined my father in South Yarra and studied accountancy at Melbourne University,"

Dan had a stint in the Air Force and at the end of World War 2 he returned to work in the family business. But just like his son Phillip, Dan was an independent spirit, he left his father to start his own business. He bought a licence in Chapel Street, South Yarra. "It was very tough in those days," he said Particularly tough because he didn't want to sell groceries.

Even now he feels sick when he goes into a supermarket. "I can't stand the smell. I suppose it is all that synthetic packaging."

There was very little wine sold. That grand gourmet and wine lover, Walter James could not understand it. Here was a country that produced wine. Why weren't we like the French, the Italians or the Spaniards? There it was the most natural thing, one went along to a store or a vineyard with a decanter or a jug and came away with it full, as if one were buying milk.

Dan thought about this and started selling wine in flagons, wine in jars by the gallon. He set out on foot with an employee and put handbills in letter boxes right through Prahran. He called it The Cellar Claret, the Cellar Hock and the Cellar Chablis. Eventually the name Claret changed to Shiraz. Even so there was not a big market for unfortified wine. Right until the early 1960s, 90 per cent of the trade was in sherry, port and muscat. Those splendid blockbusters came in by the hogshead.

It was in 1962 that wine began to take off. "It was fantastic," said Dan. "Both for me and people like Doug Crittenden. I formed a Vintage Club, the Prahran Wine and Food Society and I started importing champagne and claret. It was just incredible, people could not get enough wine. They wanted to start cellars. People with money would come to me and say, Look I would like you to give me 100 dozen or 200 dozen. Choose it yourself, but just make it good stuff.'"

Meanwhile Dan was doing very well with his flagons. The flagon on the kitchen shelf became almost as common as the box of Corn Flakes and Rice Bubbles. But Dan didn't like those huge bottles. It was a dreadful way to sell wine. Instead of rebottling the wine from the flagon, people would leave them on the kitchen shelf, half full, literally like the Corn Flakes. Then they would wonder why the wine turned acetic and progressed to vinegar.

Then they were bulky, hard to store, and hard to sterilize. The whole thing was cumbersome and labour intensive. "There had to be a better way," said Dan. "We tried everything. We tried waxed milk cartons, we tried soup cartons. But the alcohol worked on the cartons and they sank like a drunken man. We tried a new type of carton used for cream, a Tetrahedron made of aluminium foil, but the machine to make them cost hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Then came plastic, the bag-in-the-box. It was first tried in England, but with little success. In 1965 Angoves in Australia had a try, cut the corner of the plastic and put the liquor in a decanter.

But the genius, who got it all going, according to Dan, was a Geelong man, Charles Malpas. He had invented a little container which held lighter fluid, and he believed he could adapt his ideas to sealing and penetrating a plastic bag. There was the problem, the bag could collapse very nicely as the wine ran out not allowing a nasty space on top filled with air that would oxidise the wine. But how do you get the wine out the other end, without drips, without out destroying the bag? Malpas invented a bag that had two rings, one that fixed on the bag, another that fixed on a tap. This tap was pointed, push it in, it locked on to the first ring, then pierced the bag and clipped on to the ring inside. He called it "airless flow". He envisaged a plastic barrel with a bag inside.

He took it to Max Shubert at Penfolds, they called it "the triumph of the century." In 1967 the bag-in-the-box went on the market and it looked like a marvellous new era in the wine industry. It looked like a biscuit tin with a bag inside.

If it wasn't the triumph of the century for anyone in the column business it was certainly the liquor story of the decade. It made wine drinking all too easy. Just have your box of riesling, right there in the fridge beside the bottles of milk, the bag of tomatoes, and the packets of butter, and every time you feel a trifle thirsty, fill up a glass. The box of red could remain on the dining room sideboard, fill up your glass when you are walking through on your way to the family room.

But disaster struck. The plastic over a long term could not cope. It was filled with microscopic holes and the bags-in-the-boxes, which stacked so beautifully, leaked in every licensed store in the country. The mess was appalling. All boxes had to be returned and Max Schubert said he would never listen to the idea again. Penfolds sold two million of them and more than 75 per cent were returned. The loss must have been in millions.

That year an advertising agent called on Dan Murphy. He said Charles Malpas had appointed him as his agent. Why not produce the Dan Murphy Red and the Dan Murphy White, in the box. A cardboard box was the thing, he said. This was the age of 'the disposable', who wanted to be bothered with a tin? So out came the Dan Murphy pack and just like the Penfolds product, it leaked. "It was costing us a fortune," said Dan. So next they went to Japan and a Japanese firm produced a soft, lovely plastic that did not leak, all the problems were solved and at last the wine which everyone called "chateau cardboard" was on the road.

Soon Dan was selling hundreds of thousands of bags in the boxes every year, and now he had the space to sell them. In 1968 Dan Murphy's Cellar expanded into an Arcade, which very nearly made it the largest retail wine shop in the world. The Arcade was one of those beautiful affairs built in the 1880s when the boom was on and Melbourne was flowing with money. It had the cathedral-like ceiling, all the little shops on either side which made the cathedral's chapels, or perhaps even confession boxes. There was elegant cast iron lace and, of course, cellars underneath.

The Arcade's grand opening, 26 October, would have accommodated very pleasantly the invited list of around 1000, but over 1400 turned out. It seemed everyone from Toorak, South Yarra, and Prahran was there. Free champagne, Seaview and Minchinbury, flowed all night. Hundreds of cases were opened.

By midnight the floor was almost ankle deep in a curious mixture of liebfraumilch, champagne, noble Bordeaux and Burgundian reds, Portuguese roses, flagon bargain specials and coffee. The opening was designed to raise money for the Women's Association of the National Gallery. Mrs Elizabeth Summons, the Association's president looked down sadly at her satin shoes and commented: "I thought I was being clever wearing a burgundy color but they're ruined."

Dan Murphy lit the arcade with 750 watt floodlights and a bronze medieval lantern which was packed with 2000 watts of tubes. What with the strain of the lights, assorted coffee urns and the power being poured into electric guitars, the power system expired. For half an hour guests struggled from booth to booth in semi darkness and glasses were filled by the light of cigarette lighters. It was impossible to tell male from female and even when the lights came on it wasn't that easy.

When the lights did come on, Mrs Summons declared the Gallery open by cutting a chain of sausages with a pair of garden shears. Then the lights failed again, this time for one ind a half hours, but nobody seemed to mind, they were having such a good time.

It was after midnight when Dan discovered some "very nice people from Toorak" nicking off down the backstairs with cases of bottles. Larceny would be merely a nice term for it. Dan lost over 20 cases of high quality German wine that night. It was after 1 a.m. before he managed to get the crowds out of the Arcade and begin the great clean up, but everybody in Melbourne knew he had opened.

Then came the crisis. The Arcade not only had its tremendous wine selling floor space, but it boasted Dan Murphy's Restaurant, where Dan felt he had to appear every night. There was his Vintage Club which began with a 1000 members in 1961, grew to 13,000 within eight years and eventually to 43,500. In 1971, Dan had the first of a number of heart attacks. He was in hospital and David Wynn, of the celebrated wine-making family, came to see him. He brought a bunch of flowers and said: "I am sorry to do this Dan, but I have signed an agreement with Charles Malpas."

Dan would continue to sell the bag-in-the-box, but now Wynns of Coonawarra had the wholesale rights to sell all over Australia. All this should have made Malpas a multi millionaire, but there were other problems. Originally the boxes came with a separate tap. One opened the top of the box, took out a little tap and pushed it into the bag. People would often get it all wrong and end up with wine all over the carpet.

Malpas was able to patent the fixture on the bag, but he could not patent the taps. Other manufacturers designed different dispensers, taps that were already attached to the bag. So finally the only people who made a fortune out of Chateau Cardboard were the big wine companies and the retailers, but at its peak in the late 80s, 70 to 80 per cent of all Australian wine was coming by bag-in-the-box.

Dan partially adjusted his life, closed his restaurant, closed his vintage club, but nothing stopped him expanding his business. He opened a branch in Alphington, which did, literally, become the world's biggest wine store. On 1 November 1991, Judge Francis Lewis in the County Court sentenced Dan to two and a half years jail for alleged tax evasion. Dan's daughter, Clare, bravely faced the press and insisted that her father was innocent.

Dan lodged an appeal in the Supreme Court on 7 April, which quashed the conviction declaring that Dan had not received a fair trial.

Doug Crittenden, is the other retailer who has had a profound influence on my demon. He has retired several times, the first in 1983. But few people in the liquor industry are better known. Everybody knows Doug, from pensioners around Prahran through to the grand people of Toorak, the Baillieus, the Grimwades, the Nicholases and all the governors back to Sir Winston Dugan.

He leans forward just a few millimetres. That came from serving across a counter for 40 years. His nose is faintly eloquent, that came from sniffing out Australia's most saleable whites, its most generous drinkable reds and its most lay-downable ports.

He did one thing that was remarkable. He was a director of a large family business with seven stores and a turnover of millions, but always he stayed the grocer - and proud of it. He served behind the counter in a blue jacket. Len Evans never missed the opportunity to say: "Crittenden, you've got the best grocer's palate in Australia."

THis father, the famous Oscar Crittenden, started in 1919 in Glenferrie Road, Malvern. It became the most important grocery south of the Yarra. In 1945 young Douglas wanted to go to sea, but no jobs were to be had, so his mother persuaded him to join Crittenden's. "All right, I'll give you a try," said Oscar, "but you'll have to start at the bottom."

It was literally the bottom. He'd arrive at the cellar of the Toorak store at 7:30 am, light the boiler then wash the bottles. Bottles were in desperate supply, worth 10 pence a dozen. This was just the end of World War 2.

"I used to spend all day bottling port," Doug recalls. "It came down from Rutherglen. They were pretty mean with the spirit in those days and it was so young it was barely fermented. I had to leave the bottles standing up. Why? Because the corks would pop out. Grog was rationed. People would line up in a great queue and the whole lot would be gone in an hour."

Of course, a grocery was a grocery in 1945. "There was sawdust on the floor, cats to keep down the mice and nothing was packaged. You weighed out absolutely everything - tea, flour, rice and sugar. The cheese was there in a great 40 pound loaf by the counter. I'd work with a pencil behind my ear. Mrs Jones would come in. 'I'd like some jam, Mr Crittenden, what sort do you have?'

"'Mrs Jones, we have raspberry, strawberry, black currant, plum...'

"'What price, Mr Crittenden?' You'd have to know the prices of everything by heart, and you'd tell her. She would choose plum because it was the cheapest.

"'Now Mr Crittenden, what sort of tomato sauce do you have?' And so it would go on. It was another age. You wouldn't get through a customer in under a quarter of an hour."

Then it was his job to go round the district, door to door, collecting orders. The housewife would come out. "Oh Mr Crittenden, what do I need this week? Let me see, I'll just go through the kitchen cupboards..."

So he would collect all the orders in the morning, then they would be delivered later in the afternoon, sometimes with motor cycle and side-car. Some of the orders were beyond belief. There was Mr G.R. Nicholas, of Nicholas Aspro. At the Nicholas mansion, Homeden, there were at least six servants, including the chauffeur. The grocery and drink orders were just marvellous.

In 1951 Doug was desperate to go overseas to study food and wine production in Europe. Father Oscar was not keen. He said to his son: "If you really want to get on in this business you have to work behind the counter. You have to stand there and greet your customers. That's the only way you can find out what you have to buy."

Doug said: "That was the best bit of advice I ever received and I stuck to it all my life."

Oscar Crittenden died in 1954 and left the business to his children, Jack, Doug and Barbara. Doug was fascinated by wine, but he found life frustrating. Australians infinitely preferred beer, port and sweet sherry, but slowly things began to change. In the late 50s he was talking to Colin Preece of Great Western. Preece told him he had 1000 gallons of white wine, the best he had ever made. There was no hope of selling it, the wine was going to their factory to be made into vinegar.

Doug bought the 1000 gallons, thought up a name for it, called it 'Seven Oaks Riesling' and sold the lot for three shillings and sixpence a bottle. Always from then on Crittendens had a Seven Oaks and sales rose to 16,000 dozen a year.

It was fascinating to observe the businessman Doug on his rounds. He would go to South Australia, perhaps the Barossa. He would visit the vineyards and taste the wine. It did not pay to make decisions in the cellar. Cellars weave their mysterious spells, so Doug would take a bottle back to the motel and taste there. Then he would telephone and make an offer at a price which seemed absurd to the owner. The reply would be: "No, it's not on."

"'Would it make any difference to you if my order was for 4000 gallons? If you change your mind I'll be at this number until 10.30." They always rang back and said 'Yes'.

Who else had an influence? Oh yes, overwhelmingly, over-poweringly, totally to excess, Leonard Paul Evans. He first came into our lives in 1965 when he formed the Australian Wine Bureau with a job to promote wine on a national scale. He made a thousand friends and a thousand enemies. Like an old North-Eastern shiraz, he was very a potent drop; arrogant, self confident, without even the faintest hint of self doubt, garrulous, prepared to play all day and all night, witty, and unbelievably generous.

He believed in unquestioned loyalty. If Evans arrived in town he expected you to drop everything and wait on him. If you turned up in Sydney he did precisely the same. We turned up early at Sydney Central after travelling all night in the railway sleeper. As we carried our bags, looking for a taxi, there to our astonishment, was Evans with his wonderful burgundy-colored Bentley.

"All right Dunstan, where do you want to go?" Of course, it was always up to the Hunter. He had a custom it was outrageous for a human to go too many hours without drinking champagne. In Evans' company, champagne is champagne and usually vintage, not non-vintage. In the back of the car he would have a cold one, a Mumms, a Clicquot or maybe a Taittinger.

There was a particular curve in the road, a half way mark between Sydney and the Hunter. There is where he would stop. It was a tradition, out would come the Esky, the bottle, the champagne flutes, pop would go the cork, and we would toast the future.

Right there by the side of the road there was a little cairn of champagne corks, a monument, like those dedicated to Major Mitchell, Sturt and others, except Evans had created his own, dedicated entirely to happiness and goodwill.

So he came to town in the 1960s, the new wine guru. He created much jealousy in the trade, because he appeared in all the columns, and starred in all the talk shows. We loved to use him because he was such a marvellous yarn spinner. Other people might dispute this, but there is not the slightest doubt in my mind that Evans on his own sparked the Australian wine boom.

During the Evans era at the Bureau, wine consumption almost doubled. Just at this time he wrote in his Cellarmaster column for the Bulletin:

"In simple terms, you're not doing enough! After all, a measly 1.22 gallons a year. And in a country that produces truly consistent wines of high quality at most reasonable prices. Of this just over 4 of a gallon is table wine. There are six bottles to a gallon. So you are drinking on an average two bottles of table wine a year each! Two measly bottles. Yet being conservative, aware of the means of means, assessing off-days, dry-days, sick days, furiously busy days, I still reckon I average half a bottle a day. That's 182 bottles a year, fifteen-odd dozen, or thirty-one gallons! You other blokes have a hell of a lot of catching up to do."

He was lying of course, half a bottle indeed. It would have to be a whole bottle at least, 365 bottles a year, over 60 gallons.

Frequently he would come to our house, hilarious events always, but a challenge. The cellar would have been decimated during dinner to the tune of, say, four noble bottles. But that wouldn't be enough. That Cheshire cat Evans beam would spread across his face: "What's next, Dunstan?" He meant, of course, what would be the next bottle. Out would come the bottle. "Not good enough, try again?" So I would hunt everywhere amongst the cobwebs to find something sufficiently rare and exotic and bring it back for approval. That bottle consumed, "What's next?"

So we had a game. It was called "Epitaphs". What would you have on your tombstone? Evans, naturally, would have "What's Next?" I have always adopted the policy of putting on a brave front. If anyone asks "How are you?" The answer is "Never better". It is better to say that because mostly they don't really want to know. My epitaph was to be "Never Better".

Marie had a lovely line of coping with complaints from children: "Your next mother will be better", so that was her epitaph.

Evans was and is famous for his dinners. There was the famous $200 a plate dinner in February 1977. He invited eleven of the nation's top palates, plus the Prime Minister, Malcolm Fraser. All the money went to charity.

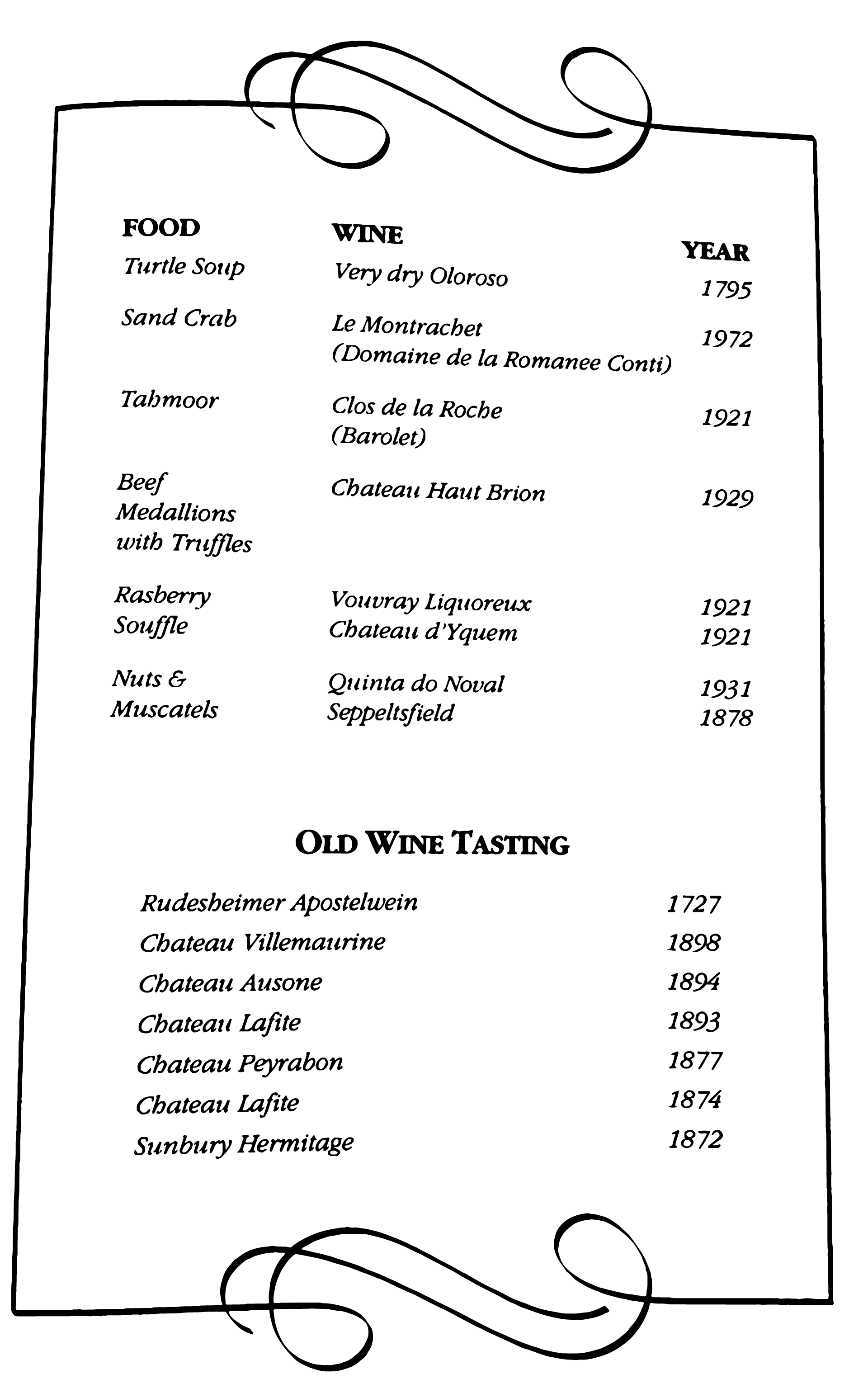

This was the menu:

He bought the half bottle of 1727 Rudesheimer at Christies in 1975 for $450 and the 1825 Gruard Larose cost $510 in 1976. There were some savage letters in the newspapers. Mrs D. Hughes of Elwood wrote in the Herald, Melbourne:

"Not only was this event discriminatory but down-right suspect. I'm tired of ruddy snobs, and the pretentious behaviour that accompanies this kind of event. If Mr Evans is sincere in giving to charity why not write a cheque for the equivalent of what this 'do' would cost thus permitting him to keep his precious wines."

Then there were all sorts of suggestions regarding the sanity of a man who would pay $450 for a bottle of wine and a miserable half bottle at that.

Evans commented in the Bulletin:

"Pay $450 for a bottle of wine! The man must be mad, but it's my money, and I don't criticise the gamblers and the questers for the America's Cup and the racehorse owners and the status seekers, all of whom, to me, spend their money other than I would. But it's their business. I just wanted to taste the wine."

Just about that time I recorded that Evans was a writer, a top wine judge, chairman of one of the nation's biggest vineyards, a raconteur, an unequalled fund raiser for charity, an authority on 18th and 17th century oak, a golfer with a handicap down around three or four, an expert on pewter and silver, his palate one of the six best in the country and, not the least of his achievements, a master teller of salacious stories. What's different now. He is well into his 60s. He has had a triple by-pass heart operation and has anything else changed? Yes, maybe he has speeded up. He is chairman of a few large wine companies, and he is constantly on the move around the nation, at lunches, at dinners, at board meetings. He makes a habit of chairing dinners in Sydney with auctions that raise nigh on a million dollars. He now paints, pots and sculpts, all with some skill.

He has moved out of Sydney and lives permanently near his beloved Rothbury Estate in the Hunter. His new place, Loggerheads, which he and his lovely wife, Trish, have created is beautiful beyond belief. There is a rose garden, a tennis court, a swimming pool, a croquet lawn, a 10-acre golf course. The house is a cross between an old English manor house and a priory. We stayed with him recently. Our room had Elizabethan furnishings. The bathroom had a dunny seat, which looked like the throne for the Archbishop of Canterbury and the shower was set in a huge wine vat.

Loggerheads is an odd name for his mansion derived from his home country in Wales but, as Len explains, there is a marvellous advantage. The visitor can say: "I spent the weekend at Loggerheads with Evans."

His recent, and most remarkable achievement, is his rotunda which has an unparalleled view down across the valley vineyards. There are six Ionic marble columns. They are vast, perhaps five or six tonnes each connected on top by a stone tiara. It looks like the Temple of Athena, at the very least a place where you keep half a dozen Vestal Virgins and call on the Oracle at 9 am daily. It is so grand, the foundations had to go down six metres.

One could go on and on about those who have influenced the Demon. There was the ebullient Murray Tyrrell, the great power of the Hunter. I remember visiting him as a young innocent, circa 1962. It was the height of vintage and the Shiraz was bubbling in the vat. I said: "Mr Tyrrell, what technical equipment do you use to tell the progress of the fermentation?"

"Ah Keith," he replied, " you don't need any of that nonsense. When you've been in the business long enough you can tell. Thereupon he stuck his arm right down into an open vat filled with shiraz and said: "You can always tell by the prickles on your skin."

There was Peter Lehmann, the son of a Lutheran pastor and the most thoroughly all round extrovert I ever knew. There used to be a rule that wineries were always open house to devoted lovers of the grape, but never on a Sunday. Sunday was sacred, a day when vignerons deserved a break from intruders.

We were touring the Barossa on a beautiful Sunday morning. Peter Lehmann was running Saltrams. I stopped the car outside their gate. The time was 11 am. I looked wistfully inside. "No, I had better not go in."

Tust then the Dunstan car was spotted by Lehmann. "Dunstan you stupid fucking bastard, what are you standing out there for? It's time for a drink."

Three minutes later the cork was out of the champagne.

Rudy Komon was another. One would call at the Komon Gallery to see the latest Pughs, Bracks or Boyds, but Rudy would say that good art should always be taken with good wine. The first time we met he opened a bottle of Hugel Alsatian Riesling which melded quite beautifully with the art on his walls.

But Rudy, always good company, was an unbending character.

He had a favourite expression; "E's a barbarrrian." His nicely honed Czech accent rolled beautifully over the Rs. A barbarian was a creature who did not agree with Rudy, a creature who did not savour the wonders of wine or the arts. In the 1970s Alan Holdsworth, editor of Epicurean magazine, held an annual dinner. There was always an award, a sterling silver ladle, for the wine person who had contributed most to the wine and food industry during the year. The rarest of foods and the most antique of wines always were produced. One year it was an ancient riesling. There had been an extraordinary find, a cache of long forgotten bottles in a cellar at Sunbury. The wine was a riesling 100 years old. It became a matter of great prestige to acquire one of these bottles. If you were on the wine social round it became a matter of great ton, as they used to say in the 19th century: "Oh yes, I thought the 1876 riesling I had with X' had a brilliant richness of fruit, but not quite the same delicacy and finish on the palate as the 1876 I had at 'Y's' house on Thursday night."

The 1971 dinner took place at Two Faces restaurant in South Yarra and I took along Rudy Komon as my guest. The chairman for the day was Douglas Seabrook, celebrated wine dealer, wine judge, and often held in awe as Melbourne's, if not Australia's, best palate. The piece de resistance for the night was a 1872 Craiglee dry red. Douglas gave the history of the wine. He said it was discovered lying in cases on the earth floor of the old winery, by his father, back in 1951.

The old wine in its handblown bottle was brought to the table. I am sure Tutankhamen's tomb was opened with none of the ceremony of the opening of this old red. Corkscrew, scalpel, everything came into operation and the process seemed to take a full hour. The cork had to be removed with no shaking and the decanting was done with such steadiness, there was almost the fear that if there was the faintest shake the bottle would explode like an Irish bomb. The wine was shared into small glasses for the 28 guests.

It was dark in colour, almost like an old port, interesting, but extreme age was there, a feeling of dealing with a cadaver. Before we moved through to the desserts, Douglas gave his comments on the wine. He agreed that it suffered from extreme age, ah, but one could detect its marvellous qualities, its fruit, its character, the gorgeous softness, etc,

Suddenly there was an interruption: "RUBBISH!" I sank into my chair, the interjection came from my immediate right, it was my guest. Oh Lord, nobody ever interrupted Mr Seabrook.

Mr Seabrook, very dignified, continued. The wine was still basically sound. There were few signs of oxidisation.

"RUBBISH! The wine is finished. Anyone can see that. The man's a barbarian."

Mr Seabrook still took no notice, but the temperature in the room had suddenly dropped from a comfortable 25 degrees Celsius to 5 degrees, and my relations with Douglas from that moment on were just a little delicate.

Another regular visitor was Dr Max Lake, who loved to stay at the Melbourne Club. Max planted his vineyard in 1963, a remarkable adventure, because it was the first new vineyard on the Hunter for generations. He called it "Lake's Folly". The first vintage was in 1966 and all his mates like Len Evans, gathered for the occasion and legend has it they foot-tramped the grapes in their bare feet while Max played Zorba the Greek on the piano. Max defied the Hunter tradition, which was predominantly hermitage, as the NSW people so charmingly called shiraz, and planted cabernet. The cabernet was an extraordinary success. He had his own special family bottling which he called "Lake's Fancy".

Whenever Max arrived in town, if you were very lucky, there was a gift bottle of the Fancy under his arm.

Max was, and is, splendid at almost everything. He was splendid in his love of music, food and wine, splendid in dimensions around his girth, splendid in conversation, and renowned as very nearly the finest hand surgeon in Australia. The Sun-Herald wrote a story about him. He never mixed his activities, during the week when he was operating he took little wine, perhaps only one or two glasses for the week. The night this article appeared, Frank Margan, Sydney journalist and later restaurateur, held a party for all Max's friends. As he came through the front door everyone chanted: "AND HE ONLY DRINKS ONE OR TWO GLASSES OF WINE A WEEK." Max beamed and took a polite bow.

My favourite story about Max was the day a young gentleman arrived with his girlfriend at Lake's Folly driving a Lamborghini. James Bond could not have been more ostentatiously splendid. This Lamborghini had 12 cylinders and an extraordinary number of carburettors. Each cylinder had its own loving carburettor collection. Max looked at this car in wonder. Could he have a little drive?

Of course, so Max hopped in, put his foot down and thereupon flooded the entire multiplicity of carburettors that lurked under its low bonnet. Nothing they could do could get that car going again. Eventually a Lamborghini expert had to be flown by helicopter from Sydney to get it going. Little events like that do not help an amorous weekend.

Who else? There's Berek Segan. Berek was born in Lida, Poland. He is short, broad, eternally ebullient, and immensely talkative. In the manner of a vintage Hollywood promoter, he calls his friends "Big Boy".

Both his parents were hairdressers and passionate about music. From the time he was four Berek was listening to Beethoven and Brahms and at six he was a violinist. At 12 he played solo on the stage with an orchestra and at 14 he conducted his own school orchestra.

Lida was only 100 kilometres from the Russian border and in 1938 it was obvious what was going to happen. Berek, 18 years old, fled to Melbourne. He was skilled at Polish, Russian and German, but knew not a word of English. He used to attend Dr Hall's English Academy which was above London Stores in the city.

He survived by playing music. There was a little trio, a cellist, Fredric Liebhold and a German, Feurstein, a marvellous pianist. But the war was on, there was no hope of making a living by music. Berek went into a timber factory, making crates, knocking in 5000 nails a day. That didn't help playing a violin by night.

Berek started his own little timber factory in the back streets of Brunswick and went on to make a fortune. In 1974 virtually on his own he started the Castlemaine Festival, which has become perhaps Australia's greatest little arts festival. But most interesting of all, Berek developed a passion for wine and steadily gathered unquestionably Melbourne's most remarkable cellar. His collection of the finest growths of France dating back to the 1920s and earlier has been a source of wonder to visitors. But the beaming Berek, always saying: "Try this one Big Boy," has been generous beyond belief in sharing his treasures, hardly drinking any of the wine himself.

His cellar is perfection, wines all air conditioned to the perfect temperature. Several years back, there was a tremor, almost an earthquake in the framework of his racks. Great wines of France crashed to the floor and the rich waterfall of famous French growths which flowed out the door would have brought tears to the eyes of every Melbourne wine lover. But Berek Segan has been one of the greatest educators because he put on show wines which few of us would have an opportunity to see.

Finally one must mention the greatest influence of all. A great palate is a gift from God. There are few of them around. Len Evans is one, Doug Crittenden is another and particularly his wife Judy. James Halliday has a superb palate. My friend Peter Walker is unerring in his skills, so too is the wonderful Hermann Schneider. I think my son, David, has a very good palate.

Alas, I do not. My memory is not good and my skills at judging wine only average. But the truth comes almost nightly when at home we look at a different wine. Or especially when we open one of our own vintages. The famed cellar palate is in danger of taking over. It is like looking at your child, there is nothing so beautiful, nothing so exquisite, as a creature spawned in your winery.

Marie, I believe, has a very good natural palate and a remarkable gift for detecting faults in a wine. She gives me a loving look, gives her opinion of the wine, and sometimes gently brings me back to planet Earth once more.